On 24th June, the United States Supreme Court reversed the constitutional right to abortion enshrined in the landmark Roe v Wade decision. It was another step backwards for a nation where retrograde motion has become normal. Campaigners note that this will not end abortion in the states that move to ban it. Rather, it will make terminations riskier - leading to greater maternal mortality - and incarcerate women for taking agency over their own bodies. As a British man, I am ill-positioned to comment further on the specifics. But as a student of America for over a decade, and a tutor of US history and politics, this reversal of Roe by a dogmatic Supreme Court majority forebodes a nation destined for Handmaid’s Tale-style dystopia and civil breakdown.

In this context, I am exasperated by the rose-tinted hold that the United States still exerts on Britain’s national imagination. It is reflected in what we teach: America is the model for comparison in Politics A-Level; the Civil Rights Movement is a symbol of enlightenment and progress - if we stop the History syllabus in 1965. For sure, the country is an extraordinary superpower to which Britain has rich cultural, linguistic, and political ties. But it is misleading to treat it as a beacon of liberty, where political culture is characterised by the high-minded ideals of The West Wing. Enamoured journalists assign media coverage to America’s antiquated customs at the behest of understanding our closest neighbours. On a recent evening, successive BBC News alerts flashed on my phone: firstly, the resignation of Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, plummeting that nation into political crisis; then the death of Ivana Trump, the ex-American President’s first wife. Unsurprisingly, Mrs Trump was our dinner table conversation. With British political norms eviscerated by outgoing Prime Minister Johnson, a cost-of-living crisis hastened by war in Ukraine, and its energy ramifications, we must now reorient ourselves away from America. Our political gaze must shift to Europe and the rest of the world.

Why now?

There are logical reasons for Britain’s obsession with the United States. Historically, it was motivated by imperialism and geopolitics. Latterly, cultural exchange, the Cold War alliance, and the so-called “Special Relationship” have proven more influential. But since 2015, the perverse entertainment value in Donald Trump’s political rise and presidency have given way to democratic decay which - while it should be covered - steals the oxygen from more consequential global developments. Broadcaster Roger Mosey upbraids a lingering 'over-obsession with America' replicated across British media outlets on anything from extreme weather to presidential nominating conventions. The focus is unimaginative, unrequited, and creates a sense that where the US might lead, the UK will necessarily follow.

In a social media age, it is important to distinguish uniquely American problems from British ones. My generation has grown up immersed in American cultural products; Instagram and TikTok collapse the geographical and institutional differences between our nations. One highlight of the Glastonbury festival came in teenage pop star Olivia Rodrigo’s performance, when she welcomed Lily Allen to the stage for a rendition of her hit 2009 single “F**k You”, dedicated to the Supreme Court’s conservatives. But there must be vanishingly few countries in which a foreign singer rolling through her nation’s judiciary by name would elicit such visceral recognition. Indeed, I was struck by how many British twenty-somethings shared tweets and reactions on the striking down of Roe. Most focused on solidarity, but some conveyed trepidation for our own abortion protections. This sense of alarm overlooks how hot-button political issues in the UK and US are of a different scale and kind; a recent YouGov survey found that just 2% of Britons would seek to ban abortion. Right-wing extremism correlates strongly with evangelical religion, and where 25% of Americans.) consider themselves “born again” Christians, less than 3% of Britons do. Our “culture wars” pale in comparison to those in the US. Luke Tryl, director of the More In Common thinktank, notes that in America, one topical opinion - say climate change denial - is a disturbingly accurate predictor of someone’s worldview. Britons, however, are ‘much more likely to approach things issue by issue.’ We must dispense with the widely-propagated false equivalence, summarised by journalist Jon Sopel: ‘if only they didn’t speak English in America, then we’d treat it as a foreign country - and probably understand it a lot better’.

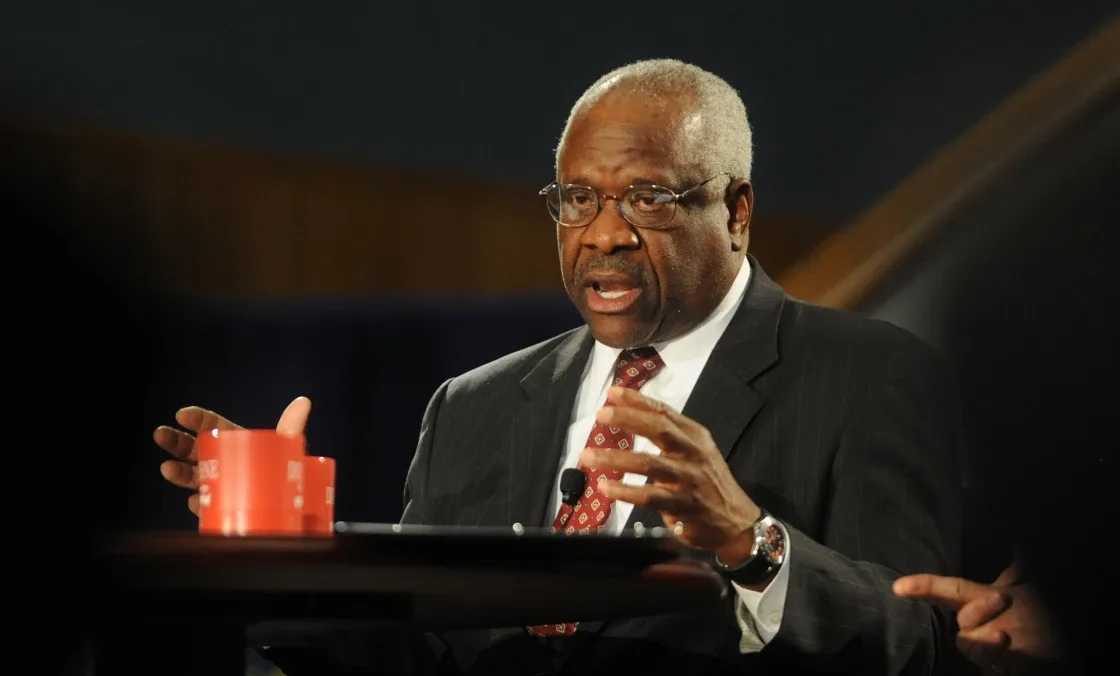

As a tutor, it feels increasingly counterproductive to teach American politics as a democratic exemplar. Despite President Biden’s efforts, I see an irreparably divided country where women, low-earners, racial and sexual minorities are not entitled to full citizenship. Trump’s greatest legacy lies in a Court that threatens to reverse further constitutional rights with tenuous public support. In his opinion on Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization - the case which overturned Roe - Justice Clarence Thomas detailed how the logic of the reversal should apply to previous rulings on gay marriage, private same-sex acts, and married couples’ access to contraception. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has pursued deregulation with alacrity. It ruled in the week after Dobbs that the Environmental Protection Agency cannot regulate coal-fired power plant emissions, thus scuppering the Biden administration’s climate targets. The Court’s unelected, right-wing Troglodytes hold America’s future hostage to an 18th century reading of the Constitution: every man should fend for himself, with only a firearm for defence. This is so alien to the British constitutional system for comparisons to be meaningless. Yet we privilege American politics over an understanding of Europe and threats further afield.

Shifting the gaze south and east

Britain seems woefully incurious about European politics. France, Germany, and the continent’s other flagship democracies scarcely featured in my politics lessons and, before the war in Ukraine, Europe’s affairs were treated cursorily by the British media. This prefigured how Brexit was handled; my recollections of the pre-referendum period are of broadcasters reporting on fraught summits from Brussels, or uncritically covering falsehoods about Turkish immigration, rather than deeper explorations of our EU membership. I found it equally baffling prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to see BBC reports take the tone of a dating show: Look at those tanks! Will Putin make a move? Find out after the break… Indeed, it is only since February that European defence and energy policies, and their geopolitical ramifications, have moved to centre stage in British news coverage.

Britain could learn much more from the continent in the aftermath of Boris Johnson’s disastrous premiership: to rebuild accountability in British politics; form safeguards for institutions he undermined (Parliament, the Supreme Court); or hasten electoral reform. Germany has thrived under coalition government and a rigorous Basic Law (Constitution) since 1949. Spain and Portugal have built resilient parliamentary systems from scratch in the aftermath of 20th century dictatorships.

Furthermore, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of European democracies allows us to recognise comparisons in the rest of the world. I recently discovered The Rest Is Politics, a refreshing new podcast from Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, both partyless British politicians with a desire to improve the political discourse - to ‘disagree agreeably’ - and broaden the discussion beyond asinine transatlantic connections. Recent episodes have ranged from Europe to Sri Lanka, Colombia, Chile, as well as the world’s most dangerous nation-states, Russia and China. In 2022, we have seen the political calculations required by Germany and much of central Europe to mitigate their dependence on Russian energy. We should similarly consider the quandaries posed by China, with its greater long-term economic heft. Is Europe prepared to defend democratic ideals in Taiwan in the way it has in Ukraine? The risk that President Xi attempts to “reunite” Taiwan with the mainland is especially acute when we consider that 92% of the world’s advanced semiconductors - integral to military manufacturing and commercial supply chains - are made here. It is imperative that we try to understand Chinese politics before Xi’s expansionary ideals take root - not in retrospect, as with Putin’s Russia.

A health warning for America

I’m not suggesting that the UK ignores American politics altogether. What is decided in the United States - still the world’s largest economy - will continue to reverberate globally. Europe’s continued military backing of Ukraine is reliant upon America’s finances and continued interest. It would therefore be counterproductive for British politicians to turn away from the US, even if our continued transatlantic partnership gives credence to its broken system. Yet at the level of media, public institutions, and private individuals, American politics must be better scrutinised. I’m not convinced that what happens across the pond will not happen here. In refusing to resign and denigrating the value of truth, Boris Johnson took a leaf from Donald Trump’s playbook. He surrounded himself with lap dogs like ten-minute leadership contender Suella Braverman, who as Attorney General pushed for a treaty that would break international law (the Northern Ireland Protocol) and described anti-Conservative tactical voting in recent by-elections as ‘a dishonest electoral pact’. We must take the lessons of democratic decay in the United States, but combine them with greater curiosity about political developments elsewhere.

America’s immediate political future looks grim. Republicans are poised to reclaim both houses of Congress this autumn and deny President Biden any substantive legislative agenda. The hearings into President Trump’s incitement of terrorism at the Capitol on 6th January 2021 have produced damning evidence, but there is no precedent to levy criminal charges on a figure of his stature. As such, his return to the White House in 2025 seems likely. For a British millennial absorbed in American politics, it is easy to fall down the rabbit hole, to see the transatlantic forebodings of doom at the expense of everywhere else. We need perspective: a focus on Europe, Russia, China, and beyond. We need a cautionary eye on US politics, not an adoring stare.

Written by

Matt JeffordUniversity administrator and pub quiz enthusiast. I'm engrossed by current affairs, reading, tennis and food, and an expert in poor political predictions.

Weekly emails

Get more from Matt

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Matt?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast