Lockdown: When "Love Thy Neighbour" meant dying alone

It has been two years since the beginning of the first UK lockdown. Initially, I remember, it wasn’t supposed to last for more than a few months at the most – my friends and I all assumed that things would be back to normal when we returned to university in September. I was even added to a group chat which was given the semi-apocalyptic name of Lil party after the end. As it happened, the end never came and neither did the party; many of the people in the chat had either graduated or were at home by the time indoor gatherings became legal again. Still, once the new semester started, I realised that my situation was infinitely better than that of the freshers whose first experience of independence involved living in prison-like accommodation and eating at tables set up in a manner which, when I saw them, brought back unpleasant memories of my old school exam hall.

University students formed one of the sections of society whose wellbeing was ignored the most. They only featured in the news to be blamed for the rise in cases in the autumn of 2020, or for a bit of sensationalism when they were locked up in their halls and fined for what had once been normal behaviour. There was a deep sense of public virtue in staying away from other people: we were saving lives, we were doing our bit for the NHS, and to break the rules showed incredible stupidity or extreme selfishness. But the narrative now seems to be changing. Even The Guardian, which consistently argued that government restrictions did not go far enough, has begun in the last months to feature pieces suggesting that lockdown did the UK more harm than good.

It is important to consider the negative effects of lockdown, for on top of loneliness, mental health issues, and the exacerbation of educational inequality, the physical isolation it imposed created a world where children’s birthday parties could be interrupted by the police, but where social services failed to detect the ultimately fatal abuse of a small boy at the hands of his father and stepmother. Somewhere, something went seriously wrong: measures implemented to save lives and preserve health stripped being alive of much of its joy and meaning, and the wellbeing of certain vulnerable groups was forfeited in the name of protecting others. It was an era in which good intentions brought about numerous inconsistencies; where reducing COVID-related deaths mattered, but where other risks, and alongside them the value of individual lives, were forgotten.

Clearly then, cost-benefit analyses matter, but on their own the lessons that we might draw from them will only go so far. To understand the contradictions of lockdown, we must consider the wider issue of how they came to be, and in what context. A key development that we were facing in the West when the virus hit us was the decline of the Christian faith, which brought with it momentous change in social and moral understandings of the human person. Religion fundamentally shapes the question of what life means and what we ought to do with it, particularly within the context of preparing for death and eternity. At a time of unbelief where scientific progress meant that life expectancy was higher than it had ever been, we had been able to ignore this issue to a certain extent. But then we were suddenly confronted with a highly contagious new illness with no known cure, and thus the fleetingness of human existence returned to the forefront of our minds.

Seeing extreme measures brought in to protect our lives through our health services, as desperate and possibly as self-destructive as they were, was therefore no real surprise. Most of us were fully in favour of them. Though Christianity may be declining, we still believe in caring for others, even to the point of suffering for their sake. Nonetheless, in a world without God, other powers naturally take His place: this time, we trusted in the infallibility of certain scientists, and hoped in our governments to guide and protect us. The centuries-old tradition of Sunday church attendance came to an abrupt halt, and the weekly ritual of clapping for the NHS was born. We used modern technology to simulate the connections that we had been denied: it was the main component in the facilitation of prolonged lockdown policies and a replacement for almost all aspects of the pre-pandemic day-to-day. However, relying on it in such a manner led to a widespread sense of emptiness. It gave us the means through which to function, but COVID came too early for us to have determined in what measure technology could, or perhaps more crucially, should, replace ordinary in-person interaction – and much less to have come to well-considered conclusions about the extent to which the state has the right to enshrine such dependency in law.

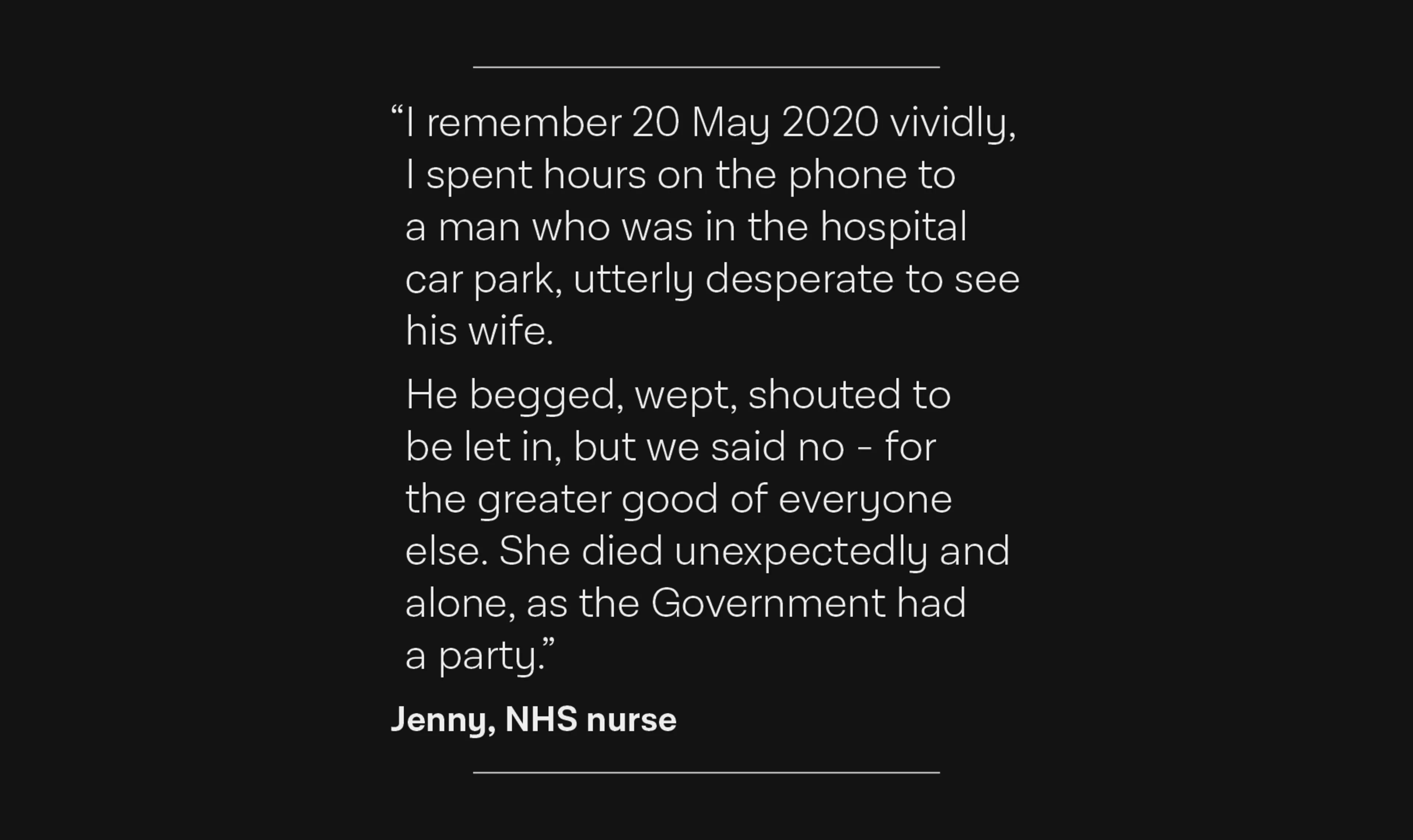

It is primarily through physical or in-person interaction that we express our recognition of each other’s inherent value; it is how we foster respect, friendship and love in their most real and fullest sense. Lockdown restrictions took that from us, but when looking at the broader picture leading up to 2020, it becomes noticeable that the previous grounding for our understanding of the dignity and worth of each human life, influenced and moulded by faith, had to a great extent crumbled by the time COVID arrived. It was, again, too soon for any kind of firm general alternative to have been established. Earlier I touched upon the idea that obeying even the minutest of rules was of grave moral concern – the skeleton of Christian virtue ethics reapplied within the body of a new age, perhaps. In lockdown, the simplicity of these timeless principles gave way to distortion when complex and personal choices became subject to general, temporary, and often confusing laws. The precept of “Love thy neighbour” was used to deny the human social disposition and turn our physical nature into a mortal threat; the greater good of reducing death rates was deemed an acceptable excuse for implementing policies that forced people to die alone. There is something profoundly disturbing about this. Somehow, as benevolent as the intentions behind these policies may have been, they refused the respect and compassion that was owed to each of those who faced the end of their lives by themselves. It is a contradiction in terms to suggest that love can be fostered through distance from others which, when so prolonged in the spirit of fear, risks dehumanising us in the end.

Where death, disease, and significant cultural shifts come together, the best option might, in a state of panic, appear to be that of forfeiting the dignity of the individual for the welfare of the majority. The need to counteract our natural frailty with our innovative power can in such times create an outlook in which the ends always justify the means. Yet, two years on from the beginning of the first lockdown, it seems to be less certain that implementing rigid COVID-19 regulations for so long was in fact justifiable. This kind of consequentialist morality cannot guarantee the making of fundamentally good decisions, whether political or personal: somewhere in these crises, a balance needs to be struck between protecting the vulnerable and preserving what gives life meaning and value. Whether lockdown was worth it or not, I can only hope that our different experiences might help us to think more deeply about what that value is.

Written by

Laura CalnanLuxembourg-born history student based in Scotland. Interested in current affairs and history's influence upon the modern world. Rarely separated from a cup of tea.

Read next

Lonely Britain: the death of the church has killed our community

Connor McIntyre

Brexited, Bored and Broken: how Britain is losing its communities

Sean Ryan

Why my generation is going insane: the impact of COVID on mental health

Matt Donno

Weekly emails

Get more from Laura

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Laura?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast