Lonely Britain: the death of the church has killed our community

22 December 2021

22 December 2021

The last live Christmas carols that I heard have melted from memory. I now only recall the collective happiness of our village, huddling together in the frosted dark, swaying in unison with the angelic choir whose hymns warmed our hearts. It’s a Christmas we see in old paintings, Victorian cards, and festive models of snow-capped villages that you find in Garden Centres. They depict an almost idyllic scene; where neighbours hand-in-hand circle a vibrant tree in shared celebration and love, later enriched during a procession in their shared space - the Church. For hundreds of years the local Church stood as a citadel of the community; where people came together, communicated, caught up, and cared. All I can do is reminisce today, listening to “Good King Wenceslas”, sung from my noise-cancelling AirPods, whilst winding down from a Netflix binge and a dinner for one. Where once my community would embrace me in fellowship, my “Traditional Christmas” playlist is left to simulate the solidarity in which I once lived. My flatmate is doing the same beyond the 2-inch wall that separates us. For this is Atheist Britain. Where the name of your neighbour is not known; where being alone is normal; where community is dead.

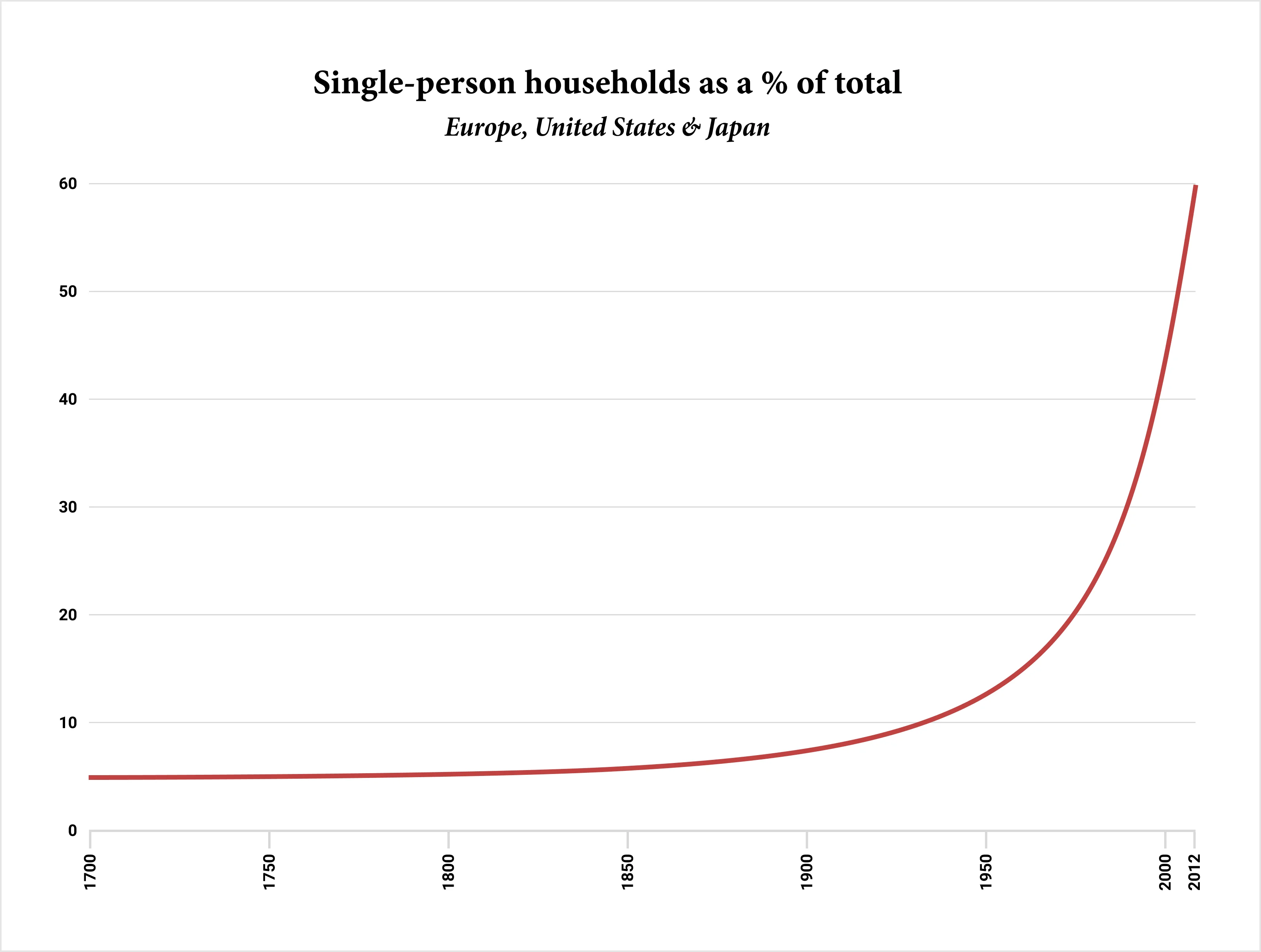

The value of community should not be understated. An animate community is integral to our happiness. From our cave-dwelling days to our modern metropolises, a strong sense of belonging is shown to reduce the risk of depression, lower the risk of heart disease, and increase life expectancy among other benefits. Yet, despite this, across the UK (and much of the west), our sense of community belonging is shrinking. Over a period of only 5 years, our feeling of inclusion has decreased by a staggering 10.1%, and our engagement within it has fallen by just under 4%; manifesting itself in fewer interactions (such as exchanging favours or stopping to talk) with our flatmates or neighbours. In consequence, a simultaneous surge in loneliness should come as no surprise. One-third of Britons now report that they feel lonely often or very often, and 13% report constant and unrelenting loneliness. It's a problem inside a vicious whirlpool. For the more our community withers, the lonelier we feel; and the lonelier we feel, the more we withdraw from our community, so the more it withers.

How can we claim to have a community when we don't even care for our parents?

The decay is so extensive now that it has made its way into our culture. I mean, quite simply, how can we claim to have a community of neighbours when we don't even care for our very own parents? Today, the two people who raised us, who care for us, and who love us, are exiled at the age of 80 to a dimly-lit domicile of depression under the pretence that they can't wipe their own bums anymore. As they are locked in and left to wallow in their harrowing loneliness until boredom and depression rob them of life, we pat ourselves on the back for posting a picture in our local Facebook group of a dodgily-parked foreign car on our sacred high street. It is a disgusting irony - an atheist might say, "It is the logical thing to do - Social Care providers are professionals" - but just what is a community for, if not encouragement, strength and support, especially for your loved ones? The reality loud and clear is that in a globally connected world we are less locally connected than ever before, and this trend is likely to continue. So how do we solve it?

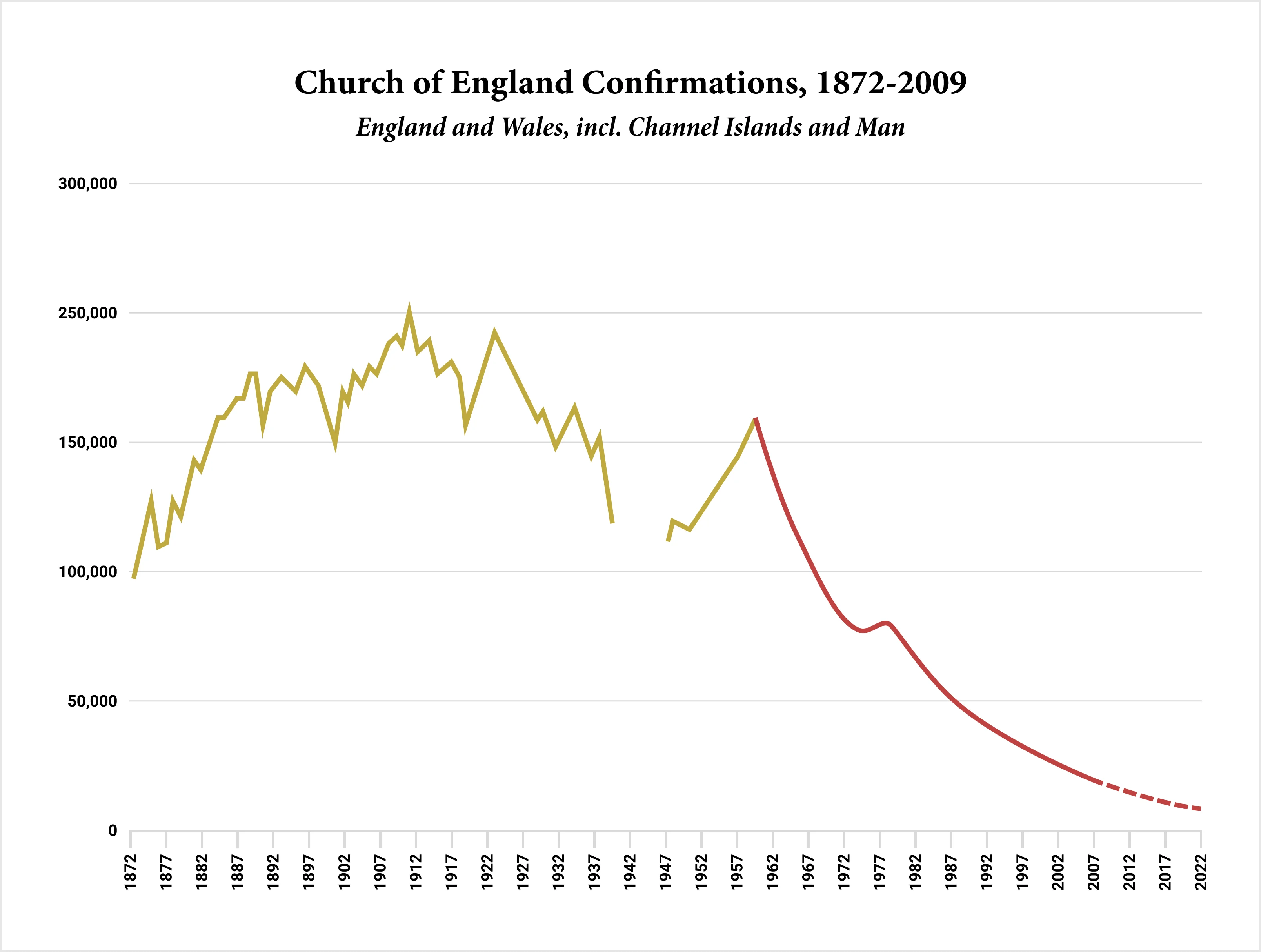

Perhaps the answer to our neglect of community lies within the church, for it lays empty. Today, on average, only 27 people per week attend a Church of England service; and this is likely to continue falling. A British Social Attitudes poll suggests that only 38% of Britons today describe themselves as Christian and as few as 1% of 18-to-24-year-olds now identify as Anglican. For us young people this will be no revelation. The Church of England represents an outdated time, and its rapid and profound decline in membership is a reflection of its sluggishness, or even unwillingness, to modernise its practices. In an age and country of science, Netflix, Instagram, and sofas, a pew to partake in the world's most boring (and, to atheists, un-factual) literature lesson is unsurprisingly unappealing. To such atheists, the loss of faith could be reason to cheer. But the demise of the church has brought the decline of British traditions and the loss of a regular company. And at a time when social media dominates our discourse, when working from home is fashionable, and living alone is cool, the value of traditions and regular face-to-face conversation with the people around us — in essence, the value of the church — is even clearer.

If the church brought us together and upheld our sense of community, then its fall has brought these values down with it.

As an 11-year-old child, despite my severe disinterest in the church at the time, I felt this value myself first-hand. Going to church was infrequent even then. I found it dull. I dreaded the hymns. And the amble there was often excessive for my lizard brain. But upon my arrival at church service, as always and irrespective of my attitude towards the place, I was greeted with a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. On one end, a grandmother entertained stories about my day and a middle-aged man fed me orange juice and snacks. And on the other end of the church, during the Bible reading, even the reverend made special efforts to spread joy to my face. Whilst delivering doctrine from the Holy book, he took out a toy tiger about the size of his palm and, at pauses in the scripture, opened its mouth causing it to glow pink and roar. It was hilarious at the time, and the young kids and I screamed with laughter to the probable dismay of the elders present; for them, the reading was a serious matter - John's words are the teachings of God after all - but the reverend took our inclusion as a priority. His trick, whilst cheap in retrospect, made us feel included, important, and even cared for by a wider people. And what better place to do so? The church brought the local people of our town together every week when otherwise they would have no reason to see each other. When they entered the church, they were transported to a place of peace; a respite from the hustle and bustle of daily life. They would congregate and catch up without contrivances or motives. There was no agenda. No "how can I help?". The ebbs and flows of each person's day-to-day were simply shared and celebrated. "How are you doing?" was not received with a one-word reply, but a genuine exchange of thoughts and feelings which extended into tea and biscuits in each other's homes. They spent time listening to each other’s triumphs and troubles, and offered an understanding arm. Skip 13 years later and much of the familial feeling towards our neighbours is gone. The only time we even see a glimpse of this "community" these days is at festivals or fayres - and those too are dissipating. Easter, Lent, Epiphany, St. Stephen's Day and Christingle (a yearly event that occurs on the last Sunday before Christmas) have all faded into obscurity. Long gone are the close-knit affairs of oranges and jelly tots, family gatherings and shared meals; replaced instead with outdoor pubs that we call Christmas markets. The truth is that with less tradition comes less culture, comes less connection to our local geography. And with less gathering comes less socialisation cross-household, and less connection between generations. If the church was the pillar that brought our people together and upheld our sense of community, then its disrepair and deterioration has brought these values down with it.

Christianity teaches us to "Love thy neighbour", but how many of us do so today?

If there is salvation, it is with the survivors of the church-going era, who are the only ones to uphold these values now. I remember fondly that, when walking back from school or church, an elderly woman named Joan who lived halfway from home and who came to the same service, would always invite my mother and I inside her house for tea and sweets. Joan was a spirited lady with a constant beam on her face and an excitable tone. Her home was as you might expect; dated and clearly Christian. Inside, we would simply sit down and chat ("High Tea", as we used to call it). On many occasions, our stay would outlast 30 minutes. Joan and my mum would gossip, laugh and listen to each other — the chatter was raw and authentic — and they both valued and enjoyed it. But it all suddenly ended when Joan passed away. My mum was visibly disheartened that day and I haven't entered a neighbours house since. The spirit of community, which blossomed from her faith, died with her — and thousands like her.

Because the church was for our community as school is for our brains; an education in how to live. And without the school and its teachers now, there is nowhere and no "how" community is fostered.

So as a young man in 2021, I often spend day-after-day inside my flat, mostly without exposure to the outside world. Most of my friends live in different cities and working remotely means that I don't see colleagues. I ring my parents once a week and text my friends once a month. Like most, I tell myself that it will get better someday, but deep down I know it won't. The whirlpool will suck me in. No face-to-face conversations means no new people, and no new people means no face-to-face conversations. Granted, some of this (or maybe most of it) is my fault. But I walked past next door's occupant the other day and he ignored me too. The effort to foster a community is a full-time job now and all of us are employed elsewhere. There is a vacant role, left by the church and, without filling it, what hope is there? Youth centres have tried. Meetup.com has tried. Maybe the metaverse will try... but with greater connection to our technology the greater the disconnection to what is in front of us. Christianity teaches us to "Love thy neighbour", but how many of us do so today?

The solution starts with our parents, our flatmates and our friends of friends. When we have a gathering we can leave seats at the table to anyone and everyone. When we eat a meal we can eat in the communal spot. When we go to the pub, we can sit with a stranger. When we are sat on the bus, we can chat with the commuter. And when we celebrate Christmas, we can turn off the television, lock away our phones and actually engage with our family. For the solution starts at home. Tradition lasted centuries for a reason; let's bring it back. For now, I'm going to take out my AirPods, knock on my neighbour's door, take a stroll with them to the church and listen to “Good King Wenceslas” live. I have a feeling that the magic will come back... or maybe it won’t.

Written by

Connor McIntyreOnline Product Designer by trade, Genetics graduate from The University of Manchester, and a co-founder of The Fledger. Advocate for open and friendly discussions on topics that matter to the young.

Weekly emails

Get more from Connor

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Connor?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast