With the war in Ukraine showing no signs of an immediate end, I have heard mutterings in the media of a modern-day Winter of Discontent.

The worst-case scenario, I hear, will look like this: a General Strike will take place towards the end of November, as inflation fails to fall as planned and workers across the public sector feel the pinch of high energy prices.

We have already seen action taken by Mick Lynch’s RMT Union, resulting in havoc on the railways during busy holiday periods. A General Strike might see nurses, teachers, warehouse workers, lorry drivers, and construction workers striking, bringing the industries on which our modern economy is built to an extended standstill.

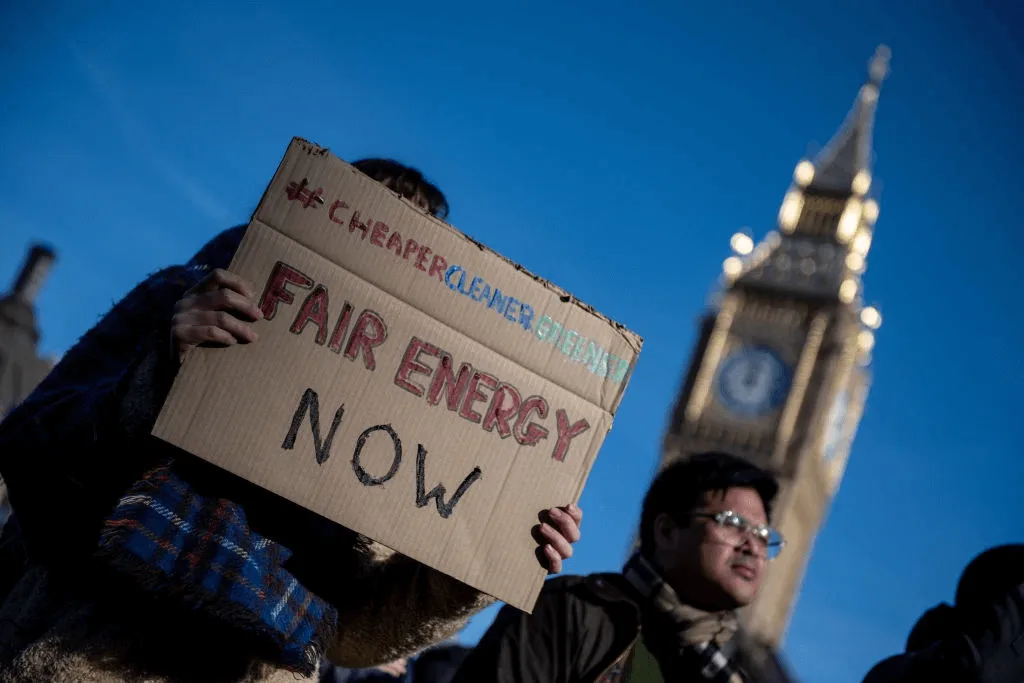

Much has been made of the price of energy, and there is a danger that not just households but schools, pubs, offices, and businesses will not see out the winter unscathed. There is even the possibility of winter blackouts around January, when the temperature plummets and depleted imports take their toll on capacity.

So I am increasingly worried that a large proportion of my Christmas will consist of seeking increasingly creative ways of keeping warm. Yet because I am young and there is excitement to be had in the face of adversity, there is no existential element to my energy crisis.

I imagine the emotion among pensioners on this matter will be of an entirely different kind however.

So the Government must step in, as it often gets the call to do.

It finds itself with three options: firstly to do nothing at all; secondly to engage in some kind of market reform; and thirdly to pay for everyone’s gas and electricity themselves, much as they recently did with the nation’s wages.

Liz Truss has, in effect, settled on a combination of the latter two. In a speech on September 8th, she set out her Government’s plans to see the country through the crisis. Her headline policy for households was a two year “energy price guarantee” that trumps the price cap and will limit annual energy bills to £2,500.

Considering the threat of Ofgem rising the energy price cap to £5,500 by the beginning of next year this will come as a welcome announcement. Without some kind of limiting mechanism on energy bills, renters, and especially younger renters who tend not to find themselves with any kind of large savings set aside, would undoubtedly struggle to pay the bills.

While the short term may seem more pressing to the average household, clearly subsidising the population’s bills is not going to work for the rest of time. As one economist notes, price controls tend to backfire, and in any case with the total cost of intervention standing at potentially £150 billion this is not a long-term strategy.

Though left-leaning economists underplay the effect government borrowing and debt accumulation have on investor confidence, it is a simple statement of fact that the Government cannot account for £150 billion of further spending after Covid spending of £310 billion. Such a move would leave young people picking up the tab for generations, on top of the student debt with which most have chosen to burden themselves.

No, complete subsidisation is not the best route to cheaper bills in the long term.

The answer will lie in intelligent reform of the energy market, specifically altering the way wholesale electricity is priced. Renewable energy in particular must play an important role.

Never mind fracking, which has always been highly contentious for its effects on the water supply and will require the approval of local communities before drill sites are given the green light.

Currently due to the high price of gas - the result of the global gas market’s high dependence on Russian gas - wholesale electricity is incredibly expensive. This is because electricity is pooled in the national electricity grid, where its source (coal, nuclear, renewable, CCGT) becomes indistinguishable.

Those on a renewable tariff therefore find themselves paying a rate heavily influenced by the price of gas, despite guarantees that the source of that energy is completely renewable. Whilst a supplier might be able to prove their energy is renewable through à la mode credit systems, the grid will nevertheless charge them for the pooled electricity that it has stored, which of course includes that generated by gas.

A reform that sees the separation of the cost of renewable and non-renewable wholesale energy seems a no-brainer. It will come as no surprise then that the Government is currently reviewing such a decision. However there is one clear sticking point: capacity.

A supplier can only claim their renewable energy is renewable if it actually is. Should the Government create a two-class tariff system where consumers have a choice between one tariff and another much cheaper, only a fool would pay more. Currently there isn’t enough capacity for everyone to be on a renewable tariff.

Not only is the issue of changing weather conditions affecting output, but for a whole range of reasons there simply isn’t enough renewable infrastructure to supply the whole country. The greenest day on record in the UK only saw 60% of its total consumption generated from renewable sources.

If the Government wanted to push renewable infrastructure development and safeguard the country’s future electricity bills, the best thing they could do is announce an intention to switch their electricity pricing mechanism to one which favours a renewable tariff. It could be done in a similar way to the commitment to ending diesel car production.

Such a change would create real competition in the market, and, most importantly, provide incentives against NIMBYism in the form of cheaper bills and for energy suppliers in the form of cheaper wholesale rates.

The alternative, of course, would be to continue with an ineffective price cap that disadvantages consumers and hampers competition between suppliers. Worse yet, a failure of action of this kind does not address the issue of our reliance on energy imports from the mainland.

Short-termism is a common disease among parliaments. Now especially, however, is not the time to repeat the early Noughties’ failure to invest in nuclear.

Forcing the market with an even firmer hand by making renewable energy the most attractive option for consumers would not only safeguard against the need for quick fixes whose purpose is to penalise in the future, but may also win the Tories votes among younger people, for whom climate change tends to be a more pressing concern.

Truss’ government holds a real chance to kill two enormous birds with one small stone. To do so might win many plaudits among bill-payers across the generational spectrum; to shy away would represent a real ignorance of the concerns of generations of young people.

Written by

Linden GriggRecent University of St Andrews English Lit graduate working in Westminster, with a fascination for politics, pub chats (get in touch), and ruffling feathers.

Weekly emails

Get more from Linden

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Linden?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast