I'm British.

India is a better country than the U.K.

28 March 2023

India is a better country than the U.K.

28 March 2023

We had landed. As I rushed off the plane, no longer bound by the constraints of the economy class seat, I was welcomed by a hot embrace and a canopy of blue, a stark contrast to the grey and monotone skies of London’s dreary winter.

I was hardly 100 metres into the airport, but the city already was already humming with vibrant energy. The visa queue was a pain but on the other side awaited a hectic streetscape canvassed with hues of green, orange, and red that filled my eyes with delight and my soul with welcome anticipation.

Brightly dressed children laughed and frolicked in the dust as the howling horns of a jam-packed bus echoed alongside the guttural roar of a tuk-tuk.

Huge domes of an ancient temple swiped by the car window as a motorcycle carrying four men whizzed by.

Everywhere I looked there was something else to captivate my attention - wandering cows, a roadside vendor with a flame of fire, women weaving cloth and a crowd of people seemingly unfazed by the chaos of life.

All while skylines were rising, motorways were extending, and factories were growing.

This was Delhi. This was India.

Like most people in the U.K., I had an outdated perception of India. When we hear its name, we think of Slumdog Millionaire and the local takeaway. But the movie is over 15 years old, and the food is fake.

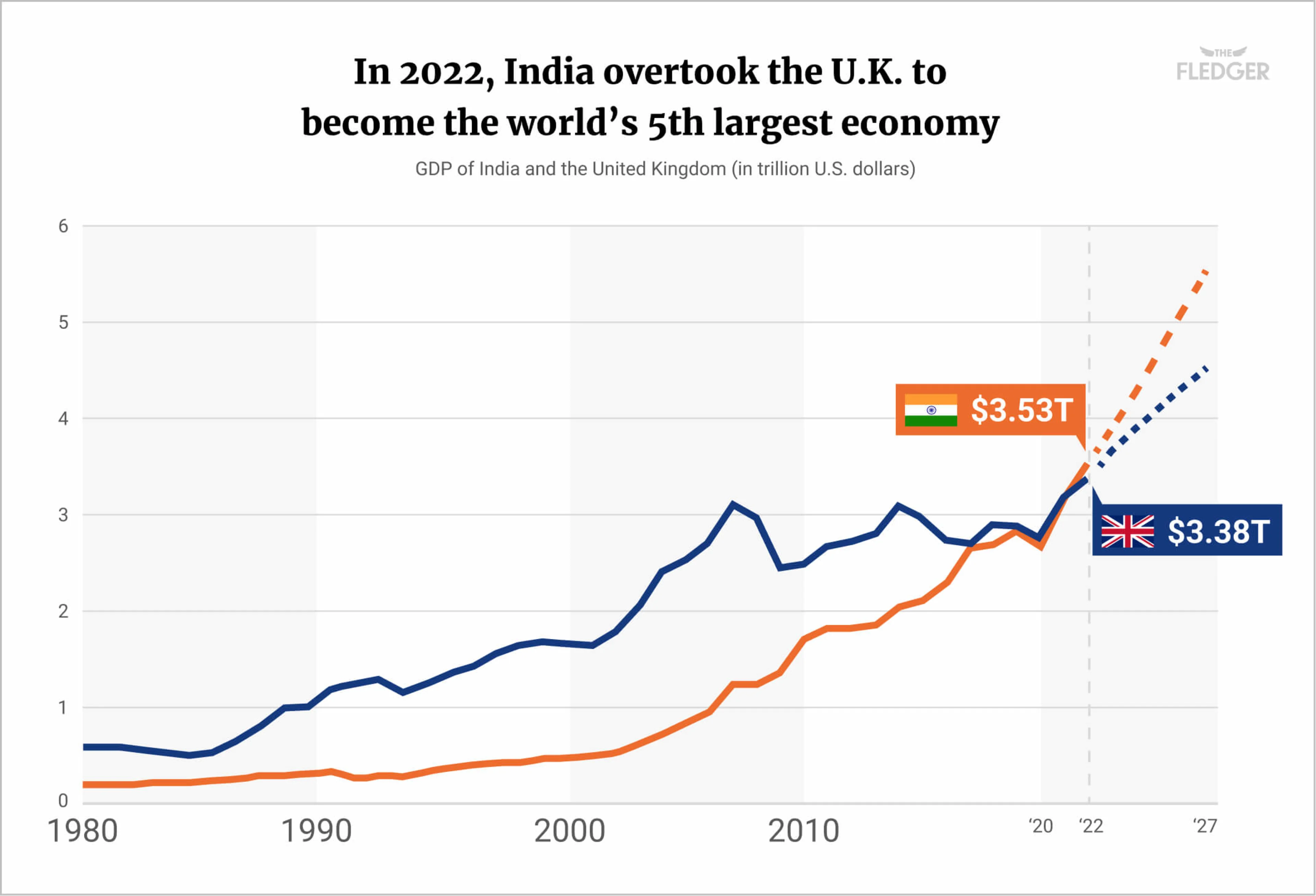

Today’s India is far removed from what we read and see on the news and TV. Through its development of a highly-skilled, ambitious workforce that includes some of the world's most talented engineers, software developers, entrepreneurs, and doctors, it is emerging as an economic powerhouse that has presented itself by quietly surpassing the U.K. as the globe’s 5th largest economy. At the same time, India is undergoing swift social progression, forging world-class universities, and booming as a cultural export; just look at RRR.

The culmination? An abundance of optimism.

The excitement of positive change fills the Indian air like the colourful scent of its superb street food – its mouth-watering smells are as ubiquitous as the promise of a better future.

It is a promise I haven’t felt in Britain since the 2012 Olympics.

In the place of hope sits a growing dread and sense of impending disaster, as if the doomsday clock is real and ticking. If the Queen’s death symbolised anything, it is this: our old empire has finally crumbled into dust, and if we young are to survive the fall, we might need to run away.

And that starts with accepting the truth. Britain just isn’t Great anymore.

Much of what we have believed to be Great about ourselves has dissipated these last few years. Our country doesn’t work properly. If three Prime Ministers in one year really wasn’t enough to start your warning siren, then surely the unprecedented rail strikes, nurse strikes, and postal strikes had your alarm bells ringing for it has revealed a shocking economic score; we are so poor that cannot afford to even pay for our carers. And it is only going to get worse. Much worse.

I don’t think you understand the magnitude of this problem. In our minds, the media’s lack of coverage often equates to stability. But covid didn’t disappear just because the BBC stopped reporting it. Our feelings and fears are a consequence of what we see. But just because the news isn’t breaking, doesn’t mean our country isn’t.

Just process it for a moment. You can’t even see a doctor. I had gastroenteritis last year and I was told to stay at home. The police are equally invisible. Sky News posts a new video of a fatal stabbing practically every other day. I was talking to a fellow Brit in a cafe in Delhi and he told me he feels safer in India. And no doubt, there is a security presence everywhere. Contrast that with our armed forces. Each year they get smaller as our debts get larger. Our grandest new warship, the aircraft carrier HMS Prince of Wales, has broken down again. Even when it works, we have to borrow aircraft from the Americans to fly off it. Just two months ago, a top US general told Britain's Defence Secretary that the U.K. is no longer a top-level force and, if called upon to fight, would run out of ammunition in a few days and be unable to protect the country. Yes, we have helped train the Ukrainians, but the Americans have bankrolled 80% of the fight and our efforts would be useless without them. It is so dire, that it would take five to ten years for the army to be able to field a war-fighting division of some 30,000 troops backed by tanks, artillery and helicopters. We are a shadow of our former selves.

Our increasing deindustrialisation, destruction of manufacturing, and impediments to business have had incredible and, quite possibly, irreversible consequences.

It came as a shock when it was revealed that the U.K. would be the only major economy to shrink this year. We are performing worse than all other economies in the G7, including Russia.

Many of the reasons include high energy prices, rising mortgage costs and increased taxes, as well as persistent worker shortages. A key factor is our ingenuity and productivity, however. We just don’t do anything anymore.

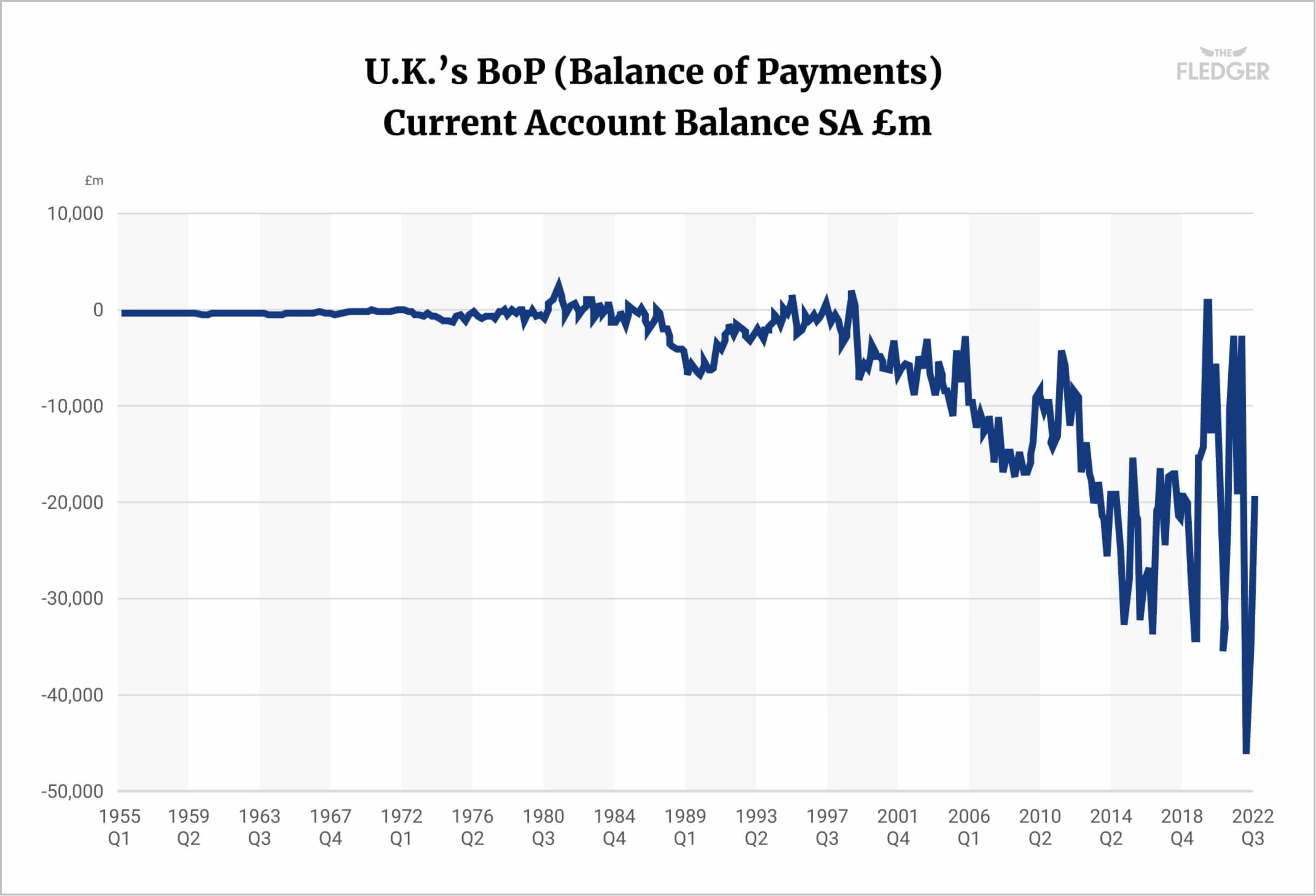

It is a simple fact that economies only grow when they create and export, and our trade balance is quite shocking. U.K. exports have decreased year-on-year and our balance of payments - a measure of our central bank reserves, net trade in goods and services, and net earnings on cross-border investments - are so astounding that it is impossible to fathom.

Many of the goods we created, including high-tech appliances, aeroplanes, ships, and cars, have ceased production. In just over a decade, UK manufacturing has lost 600,000 jobs. Dyson, Airbus, Jaguar Land Rover, British Steel, Michelin, P&O, Philips, Rolls-Royce, Unilever and more have all either cut down their manufacturing operations or left the U.K. entirely.

Tax burdens, less access to markets, production restrictions, skilled workforce supply, expensive employees, and business operational friction have all contributed to an exodus of famous British brands. And for entrepreneurs and new businesses the message is clear; don’t start a business in the U.K.

Strict IR35 rules, which deny skilled workers employee benefits; increasing capital gains tax; and higher corporation tax make Britain an unfriendly place for business. And it has shown.

It seems like everything we now do internally is contracted by a foreign company.

Why, for example, are China and France building our new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point? We aren’t building French power plants. Likewise, why is our west coast train mainline run (30%) by a train company owned by the Italian government? Why don’t we run our own trains?! We don’t run their trains. HS2, the most significant infrastructure project in the U.K. right now, costing 1/10 of a trillion pounds, has dished out individual contracts worth over £1 billion each to the likes of Skanska, a Swedish construction company. Why? Are we so incompetent? Apparently, we are.

If you don’t understand the picture I’m painting it will be because London’s financial prowess has concealed the U.K.’s overall economic weakness in innovation and manufacturing. For so long now, it has propped up the country as if Atlas was under the globe. But if London’s poor stock market performances weren’t a warning sign for future prospects, then the news that Paris has overtaken London as the financial centre of Europe will surely cast doubts on our economic future. Our transformation from industry to finance is most certainly unstable.

Our universities, in the same vein, have transformed unstably. In a flash, they have mutated from serious places of learning into hard-driving businesses, cramming in the numbers, joining the property business, and shelling out large salaries to their leaders. I suspect many British towns and cities nowadays heavily depend on these dodgy places, founded almost entirely on our debt. And for what? Why do we give them our money?

Most of us experience poor tuition in exchange for huge debts incurring increasingly vicious interest rates. And at the end, what do we have? Certificates to frame, but no special advantage in seeking the rather small number of jobs for which a degree is really needed.

The increasing saturation of us graduates vying for fewer and fewer jobs is resulting in far less social mobility. And as the cost of living in Britain continues to climb, with expenses for rent, bills, food, and socialising all shooting up, many of us just cannot afford to live now.

Take Ellie Monajemi, a care worker in Somerset who rents a one-bedroom flat with her partner: “I earn £30,000 a year and I'm still struggling”, she explains. "It's been really difficult with energy bills going up, and food is really expensive". "We can't afford to live here any more - it feels like you're backed into a corner."

How will Ellie cope as prices and taxes continue to savagely increase, I don’t know. We will just keep on getting poorer while fat cats get fatter.

Ellie, like all of us Brits, pays her energy bills to a third party (energy “provider”) that does absolutely nothing. Lest we forget, your electricity is actually provided by the National Grid. We, like her, are being exploited. Even France is taking us for a ride. EDF Energy, a publicly owned French energy company is one such energy provider. You pay them so that they can buy electricity from our government and sell it back to you. It. Is. Insane.

Yet in the midst of all this chaos and utter failure, the government does nothing.

In this idleness, how long will it be before the pound’s value falls below the dollar? We saw the very real possibility of this eventuality late last year during Liz Truss’s time in office. It almost happened. To my disbelief.

So surely now it is obvious that the notion that we are still a great and powerful country is a fantasy. Stripped away, even the one thing we hold dearest, the NHS, you must realise, is a complete disaster. The idea that is “the envy of the world” is a ridiculous self-delusion.

Early this year, official figures showed tens of thousands of cancer cases went undiagnosed as NHS waiting lists ballooned. And in England, 7.3 million people are waiting for non-emergency treatment or surgery, the highest figure since records began in 2007. That’s over 1/10th of the population being let down.

As a consequence, 500 people per day are needlessly dying.

Let’s face it. When we locked down, we didn't save the NHS. We didn't save anything. We just destroyed this already-beaten country.

The King’s Coronation will surely put a spring back into Britain’s step, but only momentarily. The coming years of heavy taxes, along with the inflation and rising mortgage rates we face, will squeeze us further, increasing divisions between people and our 4 nations. We are seeing it already with the boats. We are seeing it with #IndyRef2.

As the son of Hans Frank, the governor-general of Nazi-occupied Poland during World War Two said: "As long as our economy is great, and as long as we make money, everything is very democratic."

The Indian story is starkly different.

India quietly celebrated when it surpassed the U.K. as the 5th largest economy in 2022. Although Britain took little notice and still does, it represented an irreversible shift in the direction of global prosperity and power which will see India become the world’s second-largest economy by 2050, behind only China, to the fantastic fortune of its young population.

And such fortunes are already starting to show their face.

In an imbalance that varies state-to-state, almost one-third of Indians across all ages, incomes, and social groups are now considered middle class — of which 14% is lower middle class and about 3% is upper middle class. These people enjoy a comfortable lifestyle; a car, occasional meals out, and annual “vacations”.

While this suggests that two-thirds are working class, only 3% of Indians are actually living in relative poverty owing to the incredibly inexpensive cost of living.

And what’s miraculous is that this change seems to have happened almost overnight. It was just 30 years ago when India’s economy opened up to direct foreign investment, and since, the country’s GDP has grown 14% year-on-year seeing citizens achieve better education, healthcare, jobs, and market choice than ever before. Together this has made India a more attractive destination for foreign investors, which is likely to continue to propel the country’s economic growth well into the future.

Yes, there is still a way to go. The significant income inequality within India can be quite shocking; at the high end, India is home to some of the world's richest people, and at the low end, people live beg-to-hand and hand-to-mouth. But couldn’t this be said about the U.K. too? Just take a trip to Blackpool if you want to see deprivation.

Most countries have a large wealth disparity, and being underprivileged anywhere sucks. India’s gigantic population makes it more visible, but it’s not exclusive.

The important deliberation should be about social mobility and how hopeful the nations are for future security and success. And unlike Britain, this is where India excels.

To make the point, I was in a discussion with a successful Indian businessman about prospects between the two countries. In a conversation that explored the cost of living, he concluded that to enjoy an equally comfortable lifestyle that he inhabits, he would need to earn at least £100,000 (~1 crore rupees) per year in consideration of the crazy cost of good quality food (as is standard in India); the insane rent payments; energy costs; and the freedom to have fun in life. His total was £5000 (~5 lakh rupees) per month after tax. He expected that this was totally achievable - and normal - given his, and many others, equivalent lifestyle in India. Alas, imagine his disbelief when I explained this was a pipe dream for most.

It hit home when he visited the U.K. recently and received the bill for a meal in London. “£50.00 [5000 rupees] for 3 dishes! How did you manage?”, he exasperated to his daughter, who studied here and somehow survived on ~£1000 (1 lakh rupees) per month. For context, the same food at a similarly classy place in India would cost just £16. £50 could get you a 5-course meal at a Michelin Star restaurant.

And it is precisely this reason why so many young Indians are prospering. A middle-class couple who both earn can easily pool together £1500 per month; and minus the western bills, it makes for a fantastic quality of life which will undoubtedly only improve as wages rise and food remains cheap.

There is so much happening in India that it’s hard to ignore. When I visited Delhi last January I saw the blueprints for a new motorway/highway that linked the city centre with the suburbs. Skip one year later and it is finished. It is lightning-fast development. Just a couple of months ago a new bullet train was announced… Contrast this to HS2, which has again been delayed, this time by two years. India’s educational investment and push for self-reliance (“Made In India” scheme) is seemingly paying off. It’s like Britain during the Industrial Revolution. I cannot even imagine how India will be in 50 years. It’s onward and upwards, and there is no looking back.

Despite the increasing prosperity in India, if you speak to most young middle-class Indians, they will have aspirations to study or work in the west; be it the U.S., Canada, or the U.K.

As a product of a western upbringing who has visited India, it is hard to understand the attraction of the U.K. beyond its architectural heritage and perceived lavishness; all things which can be experienced during a two-week break and, if you are a permanent U.K. resident, become positively meaningless after a short period of time; I mean, how often do you indulge in and appreciate them? Most of our time is spent watching Youtube or Netflix.

Hearing this will bruise the British ego. Our belief that we are a “great” country is founded on our ancestry and history. But the world has moved on even if we have not.

If we disregard our egos and assess objectively, just what does Britain offer that other democracies, like India, do not now?

Until recently, a significant selling point of the west, particularly London, was its high streets. Shoppers would fly in from around the world to splash their cash on items locally unobtainable. But while Oxford Street still boasts impressive footfall, almost every store on the road can be found in an Indian mall. H&M, Zara, Dyson, Hamleys, and Holland & Barrett are all now staples in Indian shopping centres — offering goods at the same price, if not cheaper. There are some notable exclusives like Harrods and Selfridges, but notwithstanding them, there is no reason to shop abroad, especially now that most of our high streets have become characterless clones.

Venturing outside the high street, we have our markets, like Spitalfields and Borough Market; and I do love these places for their food and vibe. But again, they offer nothing compelling enough to take a flight to visit them — and only locals are probably aware of them. The same can be said about our restaurants. They are wonderfully varied, but food, after all, is of undeniably better quality in India, and foreigners will have knowledge of “Fish and Chips” only, which I hope we can agree, is like eating cardboard dipped in acid.

Coupled with a cold, wet day, it makes for a depressing experience.

Yes, there are unique things about the U.K.; its “pub culture”, for example, is often cited by Britons searching for Britain’s soul. But to foreigners, these social hubs differ little from a bar. While we see memories in the corner of the inn, all they see is a table and chairs. Their attachment is to their own social hubs.

And like a pub, our culture, however we define it, is now nothing special to outsiders.

Through centuries of colonialism, much of what was identifiably British is now mundane and ubiquitous. Our language, ideals of democracy, and even our traditional dress sense are now commonplace. Our movies and music are everywhere. Who hasn’t heard of Harry Styles? And until around 15 years ago, suits were all the rage as formal wear in India; just take a look at photos of business meetings or engagement parties.

For good or bad, British culture, or large elements of it, has been assimilated by the world. It is reduced to an image of the Royal Family. Visitors flock to see Buckingham palace. But what is it other than fog or mist? Seen but unfelt. Visible but intangible. It does not permeate into everyday culture. It is heritage only.

British universities, too, now carry the shine of heritage. Like dodgy second-hand cars, they are, below their polished exteriors, underperforming heaps of junk. Aside for Oxford and Cambridge, not one is worth their extortionately exuberant fees.

On top of accommodation and living costs, which are around £10,880 (11 lakh rupees), international students, including those from India, are expected to fork out around £22,200 (22 lakh rupees) per year for an undergraduate degree; that’s almost 5 times the cost of an Indian university — and for what? Better facilities, maybe, but 5 times better education? Of course not. The top education levels in each country, from my experience, are at par with each other.

And yet, the U.K. remains a popular student destination. Despite the eye-watering fees and living costs, ~9000 Indian students enrolled in the U.K. last year.

But to dispel the notion that British universities are the best in the world, let us remember that India (and China for that matter) has a population of 1.3 billion people, resulting in overwhelming competition for education and employment.

Studying and working abroad offers a convenient solution to this competition; it is not about where young Indians are moving to, but rather, what they are moving away from.

The promise of an easier ride is alluring — and yes, our universities are easier. They may have been attractive on their own merits in the past, but alas, not anymore.

Like most things seemingly British, they don’t exist in majesty today. It’s their history and heritage we cling to.

As if Billy Mack from Love Actually, we idolise and long for our golden age. But as Britain slips from a world power to an archaic relic of its former glory, it is time to come down to reality and accept the new global truth; we can sing our old songs, but there is no crowd. We're no longer the headliners. We’re no longer Great. We’re not even good.

Britain is just a wandering ship with compassless captains. Its deck is deteriorating, its cargo bays are empty, and its passengers are going nowhere. There is no vision. There is no action. There is no future.

It’s no surprise that 1 in 3 young Britons are considering leaving the country.

When the ship is stranded, you jump on the lifeboat.

And yet, despite all its woes, nothing beats a stroll in a Royal Park, a walk through the woods, or a pint in a country pub after a Lakeland hike. Nothing feels more peaceful than an afternoon tea in an English rose garden in the shadow of a majestic Manor House hidden between rolling green hills in summer. Nothing is as delightful as pondering upon a 300-year-old book shop in a historical village in the dales, or watching the sunset on a quiet beach after handpicking mussels to eat for dinner. Outside the city, Britain’s heart still beats. But these are just memories. Who knows if they will come again.

And as I finish off this piece, back from my trip and waiting for my luggage at Heathrow, I am reminded that in Delhi, all the bags were offloaded by the time I arrived at the belt. Here, I have been waiting for over an hour and the bags still trickle in… I think that sums it up.

Written by

Connor McIntyreOnline Product Designer by trade, Genetics graduate from The University of Manchester, and a co-founder of The Fledger. Advocate for open and friendly discussions on topics that matter to the young.

Read next

I'm fed up with 'Forever'. Where's our Übermensch?

Sion Marsh

We youth are doomed. Is it time to leave Britain?

Connor McIntyre

Just what is Britishness?

Sean Ryan

Weekly emails

Get more from Connor

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Connor?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast